It is important to know where 17th-century Dutch artists found patronage. Freed from the nightmare of Spanish-Catholic oppression, Dutch artists could no longer look forward to an endless supply of religious commissions for the Catholic Church. But it worked out well. Although Protestant churches didn’t need art, a newly wealthy middle class, sincerely religious, needed works of art for their homes, orphanages, hospitals and council offices. Portraits, still lifes, landscapes and genre scenes, using symbolic images that reflected Protestant views, were in great demand.

Vanitas was a type of still life painting that was very popular in 17th-century Netherlands. So popular was it that some 100 painters focused solely on vanities and other still-life paintings. The word vanitas referred to the meaninglessness of earthly life and the transient nature of vanity: “Vanity of vanities, says the Teacher, vanity of vanities! All is vanity. What do people gain from all the toil at which they toil under the sun? A generation goes, and a generation comes, but the earth remains forever” (Ecclesiastes 1: 2-4). Thus vanitas paintings were full of symbols reflecting a depressing world view. Vanitas paintings reminded the viewer of the transience of life, the futility of pleasure and the imminence of death.

At a time when Italian art was soaring to new classical heights that celebrated Italian culture, architecture, music, women and pleasure, Dutch paintings included common vanitas symbols: human skulls; decaying fruit that could be full of creepy bugs; watches and hourglasses marked the shortness of life; wine paraphernalia and musical instruments which suggested that even joyous experiences would end in death; and lit candles, snuffed out before their time.

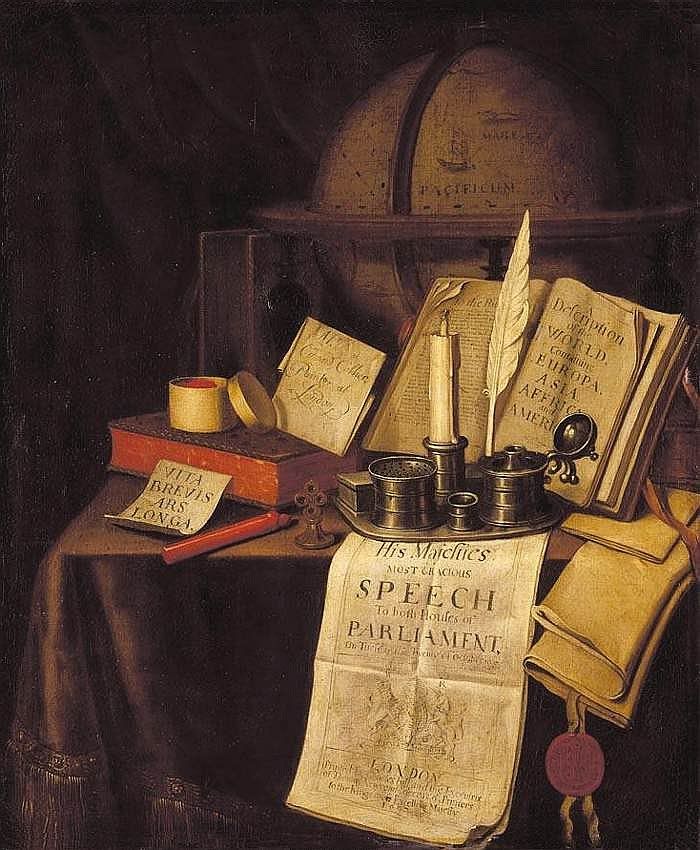

Nearly all Dutch still-lifes included an element of vanitas, even when a skull did not dominate the image. In Edwart Collier (died 1708)’s painting Vanitas Still Life (1697), the viewer noticed the implements that might be on any intellectual’s desk: ink-well and quill, candles, seals, wax, books and a globe, all within easy reach. Collier wasn’t criticising learning at all, but he was suggesting that even great learning isn’t eternal. If anything, this beautiful and detailed still life created a paradox in its very beauty. The message was consider the enjoyment of beautiful objects in a fine painting but at the same time, it warned, beware of material concerns and intellectual conceits.

It is always an interesting question as to the extent that 17th-century viewers immediately understood all the symbolism. While it is easy for any viewer to decode rotten fruit, slugs and gutted candles, some still lifes were not immediately understood as vanitas images without assistance. Another blogger suggested that there were guidebooks (e.g. Jacob Cats’ books from 1618 on) which were specifically written for viewers, to ensure they understood the symbolism. Consider a few examples. A skull was almost always understood as the symbol of death. A chronometer and a recently extinguished oil lamp marked the length and passing of life. Exotic shells were a symbol of wealth, as only a rich collector would own such a rare object from a distant land. Books celebrated human learning, while the musical instruments celebrated the pleasures of the senses. Both are seen as luxuries and indulgences of this life. Purple silk cloth was doubly symbolic: silk was the finest material, while purple was the most regal colour. Arms and armour represented both military power and superb craftsmanship, beautiful and deadly at the same time. Storage jars, glasses and carafes contained water, wine or oil; they were symbolic elements that held the products that sustained life. Further, some books on art and symbolism from this period do suggest that the symbolism in such images was often highly complex and sometimes highly personal. Although Dutch paintings from the 17th century were often sold from shops and auctions, and not via personal commissions, vanitas paintings may have been designed to fit the type of person who would want to buy the work.

Cornelis Janszoon de Heem (1631-95) painted a large (153 x 166cm) painting called Vanitas Still-Life with Musical Instruments in the 1660s. In this work, the elements were so rich that the modern viewer would be hard pressed to detect the vanitas elements. Note the “six-stringed, inlaid viola da gamba leaning against the chair, with a lion’s head for decoration and an “S” shaped sound hole (more characteristic of violin). Next to it on the ground are two types of lutes, a trumpet, a flute and a mandolin; in a chair on the left, a violin, a bagpipe and a small pocket violin” (Emil Kren and Daniel Marx). Also note the fresh, ripe fruits and domestic objects wrought from precious gold. Only the snail on the ground, the half-eaten fruit left to rot and the upturned objects tell of a sombre future for the family.

So why musical instruments? The admirable things in Dutch life were of course leading a moral family life, participating in the parish church and running a successful, honest business. But active book learning, appreciating music and appreciating flowers were all much loved and valued as well. So these last three elements lent themselves to comment about the inevitable passing of life. Musical instruments created sublime sounds and emotions, but in the end they symbolised the ephemeral nature of music. Sometimes the precious instrument was left lying on the ground or carelessly propped against a table, another suggestion that the care once lavished on music would eventually turn to neglect.

The details of the instruments themselves might be well worth studying; e.g. read the excellent article “Iconography of Dutch Recorders, 1660-1760” by MC Jan Bouterse. Richard Leppert’s book, The Sight of Sound: Music, Representation and the History of the Body, focused on expensive materials (exotic woods, ivory, silver) being used in the instruments, both to impress viewers and to create better quality music. The Hoogsteder Exhibition of Music & Painting in the Golden Age, held in The Hague in 1994, was later published in book form.

Occasionally modern writers will find in the shapes of the instruments analogues to the human form. But I find there is no evidence for thinking that anyone in 17th century Netherlands considered such analogues relevant in the vanitas paintings. Musical instruments stood for the passing of time and the fleeting nature of beloved pastimes, not for immorality. Music was absolutely celebrated in all these 17th-century works, not condemned, even though a clear warning to the viewer about the passing of time was attached.

Author: Helen Webberley